Guided By Forces of the Unknown

An Interview with Dr. Elmar Gruber on the Collecting of Mediumistic Art

Dr. Elmar Gruber is a psychologist, writer, and a collector of numerous and far-ranging works by mediumistic artists. Dr. Gruber’s extensive collection can be viewed online at CoMA, the Collection of Mediumistic Art, and on the website’s Instagram, @collectionofmediumisticart.

As an artist investigating my own strange experiences and the ways they have influenced my work, I found myself researching areas where occultism, spirituality, and the paranormal intersect with art history. In my journey, the most endlessly fascinating meeting place for art and the unknown was found in works referred to by scholars and collectors as mediumistic art. This is a particular subset of art, made outside of traditional institutions, where the artists claim that their work has been created through them by another entity or force. For these artists, like the famous Hilma af Klint, they are not the lone authors of their work. The mediumistic artist is not the primary creator but rather the tool, their hands guided by forces unknown to make the work.

Dr. Gruber’s website and collection provided invaluable resources for my own writings and presentations on this subject, and I felt it would be an invaluable experience to speak with him on the many astounding mediumistic artists in his collection. The interview I am presenting here with Dr. Gruber touches on a rich array of material on the topic: the psychology of Mediumistic Art, the unique experience of collecting this form of art, Mediumistic Art’s influence on Modernist art movements, the unlikely relationship with UFO phenomenon, and the fraught nature of the term, mediumistic art, itself.

-Alessandro Keegan

Alessandro Keegan (AK):

What inspired you to begin your collection of mediumistic art? Who were some of the first mediumistic artists to grab your attention?

Dr. Elmar Gruber (EG):

In fact, I drew and painted excessively myself in my youth and at one point considered attending art school, but then decided to study psychology because of my intense interest in all things paranormal, transpersonal, inexplicable. In any case, because of my own love for art, I was immediately drawn to mediumistic art when I first heard about it. At that time, I was especially fascinated by the classics, like Victorien Sardou, Hélène Smith, Augustin Lesage, Madge Gill, Heinrich Nüsslein, and Emma Kunz. Hilma af Klint was not yet known, and Georgiana Houghton had not yet been "rediscovered". I began to collect rather accidentally, because several mediumistic artists, whom I met, gave me some of their works. Then, still at a young age, I came across, just as accidentally, a few extraordinarily rare and fascinating works created around 1900 and in the early 20th century, which I was able to acquire.

AK:

Often the term “Outsider Artist” gets argued over. Many see it as controversial and prefer “Self-Taught Artist” or other forms of designation. How do you feel about the term “Mediumistic Art”? Is it adequate to define this field of art?

EG:

This is a question that deserves a long answer. I will try to be brief. The issue of appropriate conceptual delimitations is a tricky one. There is no escaping the necessity of taxonomy, of being able to classify and categorize to facilitate meaningful discourse. But here we are looking for demarcations and labels, so to speak, where the boundaries are so fluid that labels never capture the full extent of what needs to be labeled. In any case, what is crucial is that all mediumistic creators feel at the mercy of an impulse that they cannot escape and which they describe as a force coming from outside. This is the irreducible aspect of the phenomenon. According to this, the creator is above all only an executive medium. Although we must be careful in this regard, because the cases of drawing and painting in trance in a completely unconscious manner under the guidance of an external force are rather rare or tend to manifest only at the beginning of the development of a mediumistic artist. It is much more common, as Maggie Atkinson has convincingly shown, that mediumistic artists tend to produce their works rather in collaboration with disembodied entities. Therefore, the term "mediumistic" is appropriate but should be used with caution.

There is an additional problem posed by the fact that, from an art historical perspective, mediumistic art has been appropriated by Jean Dubuffet and his ideological framework of “Art Brut”. As a result, attention has been focused on only one aspect of mediumistic art, i.e., the more raw and naïve type of obsessive or stylistically sketchy works representing rather a form of a quasi-infantile automatism resulting in what André Breton called the “captivating stereotypy”. On the other hand, there is also a highly cultivated aspect of mediumistic art, often but not exclusively by professional artists who became mediums and in states of trance-like absorption, radically and unintentionally changed their style as a result. What they produce is a highly idiosyncratic and sublime virtuoso art. The two forms of mediumistic art differ in their aesthetics and their complexity, and are not connected by the same culture, nor by the same inspiration.

AK:

I imagine there are some challenges to collecting the kinds of artists that you are interested in. Sometimes these works are unarchived, lost and forgotten and suffer from conservation issues. What are some of the challenges you have experienced in collecting? How difficult is it to gain access to the art of some of these works, both from the past and the present?

EG:

The main challenge lies primarily in the fact that only a few mediumistic artists perceive themselves as artists at all. If their work is created in the Spiritualistic context in the narrower sense, then they work in a framework that hardly reaches the public. Since they deny authorship of the works, they often do not want to part with them, understand their value and meaning differently than from an aesthetic or artistic point of view. This is also true for the works of contemporary mediumistic artists. That is why many such works remain in closed circles, disappearing, as it were, from the public eye before even getting there. This sometimes happens with the works of mediumistic artists who, at some point, have experienced a high degree of publicity during their lifetime and have even achieved fame. It was a coincidence that the works of Georgiana Houghton, for example, famous for a short period during the late 19th century, did not fall into oblivion forever. On the other hand, from the great number of mesmerizing drawings produced by Therese Vallent, Wilhelmine Assmann and Frieda Gentes, all of whom achieved great international fame around 1900 with numerous publications, exhibitions, and public demonstrations, only one single work by Therese Vallent is known today – fortunately enough it is part of my collection.

With contemporary mediumistic artists, the biggest challenge for a collector is to find an appropriate approach to make them aware of the value of their works from a different point of view. This does not mean that I consider mediumistic art mainly under the aspect of art, let alone the art business, but rather to make the mysterious content of the numinous visionary and mediumistic dimensions visible and experienceable in exhibitions especially through the interaction of the works of many mediumistic creators. Through my background I have the great fortune to get to know such artists who often work in seclusion and usually I manage to build a good relationship with them. Many friendships have been formed this way with years of ongoing exchanges.

As I mentioned earlier, that's indeed how my collection started. I did not intend to collect mediumistic art. But the friendships that developed meant that many of the artists eventually gave me their works because they felt that they were in the right place with me and in the environment with works of other mediumistic artists. Now I had, as it were, a mission to set up a collection, in which the works can resonate with each other. I certainly understand this as a commitment, a very rewarding commitment, I would like to add. I didn't look for the collection, the collection found me.

Incidentally, I also feel it is part of this commitment to research the lives, ideas, and worldviews of mediumistic artists who have been completely forgotten and to make them accessible again. I spend a good part of my time researching in libraries, archives, and collections, as there are some extraordinarily exciting creators in my collection who are virtually unknown, such as Gertrude Honzatko Mediz, Nina Karasek or Werner Schön.

AK:

It is my understanding that you have worked as a research psychologist looking into the area of paranormal phenomenon. Has this research provided you with a unique insight into the experiences of mediumistic artists? Has exploring mediumistic art affected your views of the paranormal or, conversely, has the paranormal lead you to see mediumistic art differently? In my own experience, for instance, I connected with the idea of mediumistic art because I had multiple experiences in my past that were unexplainable and then these experiences acquired an entirely new meaning when I learned what mediumistic art was.

EG:

It is interesting that you should ask that. In fact, way back in 1982 I published a paper in a journal discussing the structure of mediumistic art as a paradigm of the structure of the paranormal. Yes, indeed, my involvement with research in parapsychology has shaped my understanding of mediumistic art and vice versa. Many mediumistic artists report various paranormal experiences in their lives. They are often more open overall to the realms of a hidden reality, have special antennae for synchronicities, premonitions, telepathy, clairvoyance. At times they live in their own world of strange correspondences up to the point of creating their own personal mythologies. Knowing the range of paranormal and transpersonal experiences, helps to better understand the mindset of a mediumistic artist. However, the experiences during the artistic processes are very different after all. Most mediumistic artists cannot adequately describe what is happening to them; they do not have the proper arsenal of verbal expression. Their form of expression is their artistic activity. Interestingly, I have often come across the fact that during their creative process it is obvious to these authors what is happening. Everything lies open before them, as it were, like a revelation. It is woven into the flow of the creative process. They are convinced that all one must do is to observe what emerges in their art. This is reminiscent of peak experiences, of mystical experiences be they drug-induced or not. Everything is there, the unfolding of the ultimate mysteries of the universe, but once they have stepped out of this state of complete absorption, which is characteristic of their artistic activity, no adequate language to communicate the experience remains.

Studying these experiences has taught me that the scientific method is only of very limited use in gaining a deeper understanding of them. This was a major reason why I withdrew from scientific parapsychological research and relied on widening my own approach to these realms experientially mainly through intensive engagement in methods of meditation.

AK:

Would you say that mediumistic art is a global phenomenon? Who are some of the artists in your collection who are from outside of the context of western culture and religion? I ask this question because it sometimes seems that mediumistic art is thought of as being largely tied with Spiritualism, the communication with ghosts, and ideas that seem to come from a specifically western cultural context, but I know there are many artists from diverse backgrounds and belief systems who receive visions, create work, and serve as mediums in some way.

EG:

For a very long time, mediumistic art in the narrower sense was associated with Spiritualism, and thus quasi-forcibly with a religious movement that originated in the West and spread mainly there. But this is wrong. Mediumism is a global phenomenon, known in various forms among all peoples and cultures. Hence, artistic expression based on visionary experiences is a worldwide phenomenon. Entity experiences and other visionary encounters at the basis of such art are cross-cultural and historically widespread. They ought to be understood as part of a broad spectrum of anomalous experiences ranging from shamanism, spirit possession, ecstatic mystical experiences, dreams, hallucinations, out-of-body experiences, and otherworldly journeys.

Nonetheless such types of artistic expressions have received little or no attention as a form of mediumistic art. Perhaps also because especially in indigenous cultures everyday life and the spiritual foundations of the peoples are so closely interwoven that artistic creations characterized by ancestors, spirits, visions, and the like belong quite naturally to the cultural heritage and are not regarded as something extraneous.

AK:

Two artists who you have written about, Victor Emanuel Bickel and Alexandro Nelson García, have connected their mediumistic experiences to UFO related phenomenon. Is this unusual among mediumistic artists, in your experience? Some people might be surprised at the connection between mediumship, which seems very spiritual, and the UFO phenomenon which many see as being very technological.

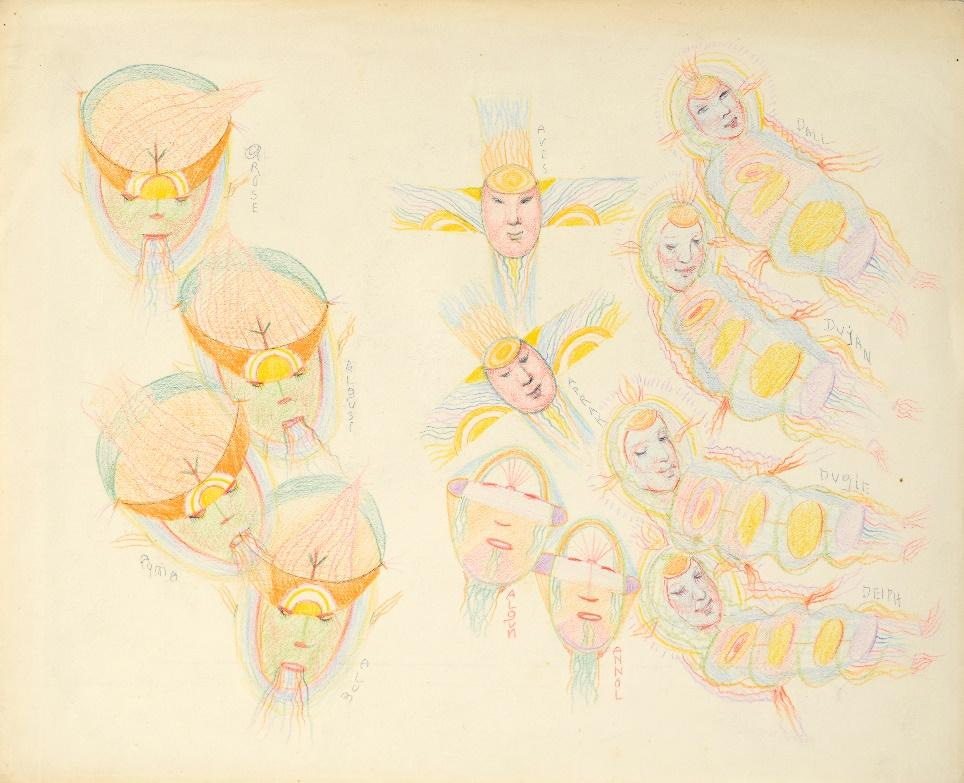

Victor Emanuel Bickel (Faroxis), Untitled, c. 1970

Color pencil, pastel and ballpoint pen on paper

49.5 x 69 cm | 19.5 x 27.16 in.

EG:

Mediumistic art is never created in a space that is entirely free of cultural influences – as Jean Dubuffet envisioned it as the ideal state for the Art Brut artist. We can discern in most mediumistic artworks a temporal and cultural context that informs the “style” of the works. It is not surprising that as technology advances, the spiritual dimension also seeks new spaces of experience. There is, after all, a line of tradition that cannot be ignored. Spiritualism is largely based on Emmanuel Swedenborg’s 18th century extraterrestrial fantasies and his visions of the afterlife. Swedenborg made ideas popular about the nature of the afterlife existence, the dwellings of angels and higher beings. The otherworldly were imagined existing in incarnate and discarnate forms in their abodes on other planets. On visionary journeys Swedenborg explored countless celestial bodies and their inhabitants and taught that spirits of the deceased existed everywhere and spread the teachings of God and Christ throughout the cosmos. From this developed the idea of the spiritual advancement of souls in a gradual process of successive re-embodiments in the form of planetary wanderings.

The somnambulists, who were put into magnetic trance by mesmerists everywhere at the turn of the 19th century, reported about their journeys to the moon, planets and stars and described what they saw as the dwelling places of disembodied entities. During the first third of the 19th century, related ideas about the physical makeup, fauna and flora, and the conditions of existence of the spirits of the deceased on other celestial bodies became entrenched in popular belief through these visionary journeys of “clairvoyant” somnambulists. Their reports popularized a spirit world that was portrayed as a reflection of earthly circumstances.

These ideas directly influenced the earliest mediumistic pictorial works in the context of Spiritualism. They consisted mainly of flowers, plants, organic structures, animals, and entities located on planets or other celestial bodies. In these dwelling places of the souls in the afterlife entities exist, which never incarnated on earth. Therefore, the notion of higher beings or other, higher developed civilizations was informed by the Spiritualist undercurrent since a long time.

In addition, there are interesting parallels between psychedelic entity experiences with entity experiences in other contexts, such as religious and spiritual visions, shamanism, mediumism, and so on. These include encounters with entities familiar from folklore and mythology, such as gnomes, dwarves, elves, but also of encounters with unidentified flying objects. How to classify these entity experiences, what underlies them, is still largely unexplored. Nevertheless, the parallels among them are often remarkable. I find the varieties of these experiences as they express themselves in mediumistic artworks quite fascinating.

AK:

Some historical mediumistic artists, such as Emma Kunz or Hilma af Klint, are very well known today, but the many mediumistic artists today who are alive are lesser known. What are some of your favorite living mediumistic artists who are producing fascinating work today?

EG:

As everywhere in the field of art, there are great qualitative differences in mediumistic artists. Artists who have created an independent, intriguing, and comprehensive oeuvre are rare among the mediumistic creators, such as Augustin Lesage, Madge Gill, Hilma af Klint, Georgiana Houghton, Emma Kunz, Wilhelmine Assmann, Margarethe Held, or Heinrich Nüsslein. The 20th century saw the activity of some great mediumistic artists whose works remain to be appreciated or even discovered, like Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz and Nina Karasek mentioned before.

Among contemporary mediumistic artists I am intrigued by the works of Noviadi Angkasapura from Indonesia, who creates his mesmerizing drawings under the influence of a supernatural entity.

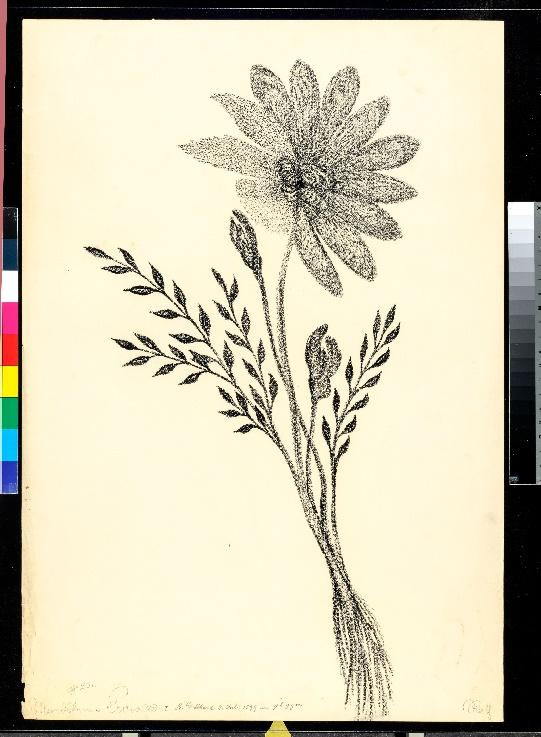

Noviadi Angkasapura, Untitled, 2015

Ink and graphite on paper

40 x 30 cm | 15.7 x 11.8 in.

Marie-Jeanne Gil, a psychic from France, began to draw following a vision of the prophet Elijah. Her intense structures of cosmic eruptions and faces of masters are filled with sprawling rays of light and exuberant colors. Unfortunately, she prefers to live in seclusion and not exhibit, let alone sell, her works, which completely cover the walls of her apartment like wallpaper. The works of the Finnish mediumistic artist K. Tschährä are also quite captivating. I follow her since she spontaneously started last year to draw “under influence” and actively exchange with her about her reflections as the process develops. Also peculiar is the work of Patricia Salen, which exerts a fascination all its own and, incidentally, Patricia is one of the few who knows how to introspectively reflect her creative process with profound yet demanding intellectual clarity.

There are quite a few others that probably work somewhere in the hard to define border area between the mediumistic and other forms of inspiration and which I find very exciting, but who at times reveal little about their spiritual backgrounds.

AK:

Are there any major exhibitions or projects that your collection will be involved with soon? Are there any announcements or upcoming publications to look forward to?

EG:

For a collector, it is a stroke of luck that mediumistic art is currently so highly valued and becoming reassessed in an art historical context. That is why there are always requests for loans. I can be selective in order to offer works from my collection an appropriate framework to be shown. In fact, at the moment there are two projects under evaluation that are truly significant, but since nothing has been finalized yet, unfortunately I cannot give more details about them. What I can only reveal in a hint is that I have made another significant discovery of a group of historical mediumistic works of utmost importance. Since one of the projects is being planned with these, I must keep all the details to myself at the moment. Isn’t it nice that there always is a veil of uncertainty and mystery spread over this kind of art!