On the elaborate pendant of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun, there is a delicately carved scarab made of the most unusual yellow-green stone. This stone glows with inner luminosity, like an irradiated honey droplet, an amber bead filled with prehistoric pollen, or the golden fruit bodies of a jelly cup. This scarab is made of a stone called Libyan Desert Glass, it is about twenty-nine million years old, and it was formed, so it seems, when a meteorite impacted the earth and heated the quartz material in the ground to over three-thousand degrees Fahrenheit, a temperature beyond that found inside a volcano. The Egyptians were aware of the rarity of such materials, if only intuiting their marvel from the fact of their rarity, or that the wonder of such transparent stones was that they seemed to be solidifications of light, liquid, air, and star-fire itself, making them the most fantastic of nature’s displays of craft. The scarab, associated with Khepri, god of the rising sun who was depicted as a dung beetle or a man whose face was a beetle, was a form of amulet so popular in the ancient world it has been found not only in Egypt but in lands all along the Mediterranean coast. In this pendant, the scarab beetle is placed on the body of a falcon, a symbol of the sun and of Horus, the falcon god of kingship, protection, and healing. The scarab holds aloft a cosmic barque, or boat, on which the wedjat eye, or the left eye of Horus floats. The wedjat eye supports a golden crescent moon and silver moon disk, in which we see a low-relief image of Tutankhamun protected on either side by the god Thoth and the sun god Ra-Horakhty.

Stoking the mystery around the meteoric glass scarab found in the amulet is the presence of another cosmic, ritual object in Tutankhamun’s grave. This is a dagger made of iron, produced at a time centuries before the ancient Egyptians were known to manufacture iron. This iron is high in nickel content which is a sign that its origins were not from this earth. This was a metal amalgamated by the collision of cosmic debris, a type of metal only found in the compositions of meteorites. Like the scarab, the metal of Tutankhamun’s dagger seems to have been the product of material striking the earth from space. This, it should be said, is not uncommon in the Bronze Age; examples of meteoritic iron used for beads, tools, and ritual objects can be found among a range of cultures concurrent with the ancient Egyptians. Nevertheless, it should give you a moment of pause to consider that such materials were among those sought after by the Egyptians for the burial objects of kings.

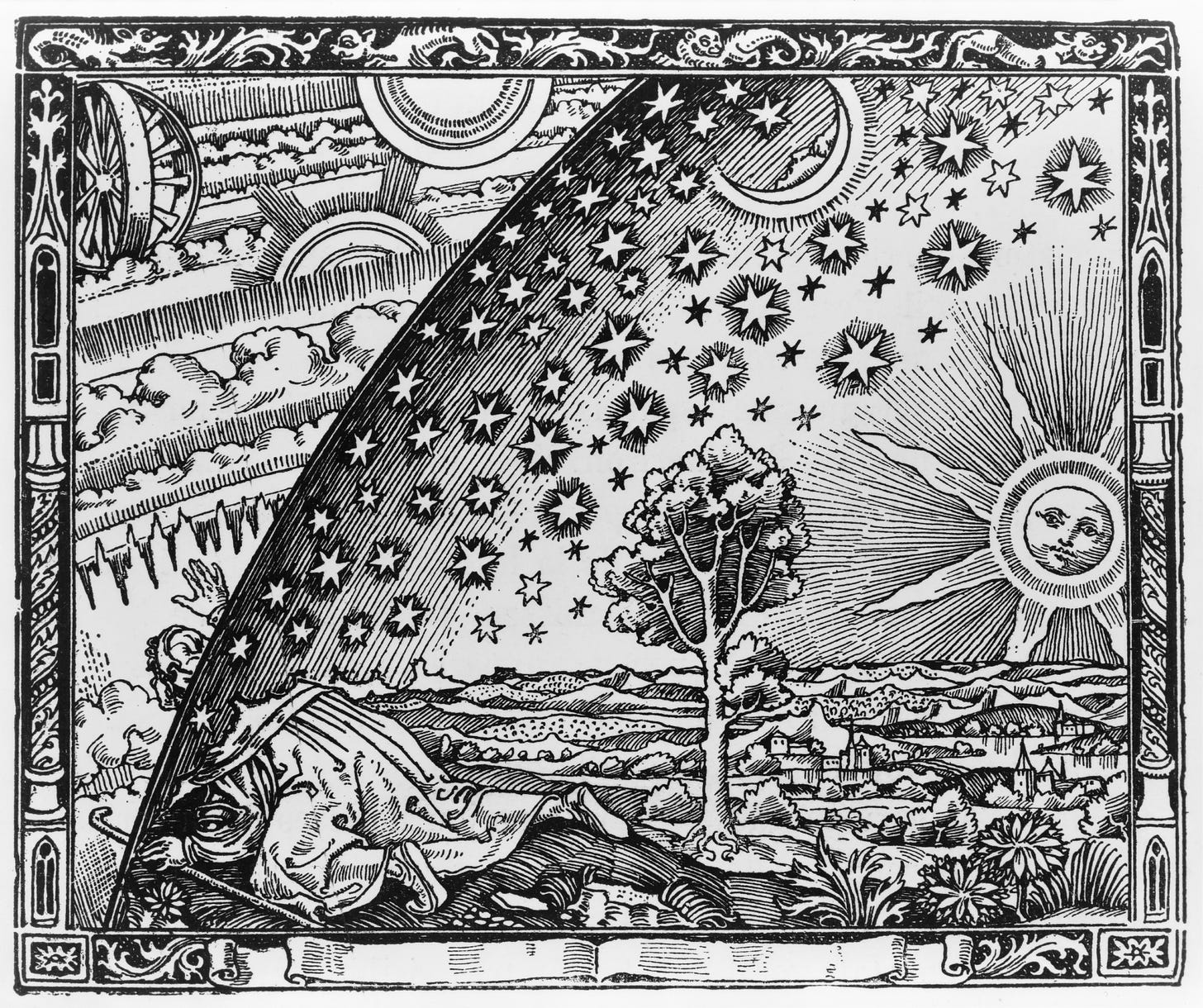

These cosmic materials, meteoric glass of the desert and iron born of blazing force, are intermingled with the treasure taken by the king to the afterlife. If the fiery vehicle that delivered these materials into the world was not comprehended by the Egyptians, because otherwise we would have to entertain that they had a science far in advance of anything before the twentieth century, then we must imagine other ways in which these substances were understood by them as being special. The glass and the iron of meteoric impacts are rare in the world and so perhaps there was some understanding for the ancients that these materials did not come through the earth like any ordinary stone might. Crystals of frozen sunlight and ores of angelic strength could be said to have fallen through the doors of time and space itself, into our world of more common substances. Any stone, metal, nectar, animal, or plant that came from the world of the gods would be as magical as a fallen spacecraft. Throughout time this thought has preoccupied the esoteric: that the material of the godly realm can enter into our own, and in so doing, it announces to us that abode of the gods is a place just as substantial as our world, but with no visible course to get there.

The god Khepri is the scarab, the dung beetle, occupying a lowly position in the hierarchies of the desert ecosystem. The scarab is a coprophagous, a creature that eats feces. It rolls the dung of animals into a ball and stores this black orb below the ground where it can spend days subsisting off of it. Scarab mothers-to-be will roll a pear-shaped ball of dung in their underground lair and nest a single egg inside the ball; when the young are born, they will survive by devouring the dung that they are sheltered in. When the Egyptians first beheld with wonder the perfect sphere of the dung beetle, a remarkable work of craft, like a black moon, they could not help but see a symbol left by nature like a painted trail marker. The scarabs would push their orbs of dung across the white sand just as the sun would traverse the sky from east to west; and so, it was believed a message was being imparted, through the magickal language of correspondences, what is sometimes called the language of the birds, about the force that beckons the sun to return each day. If there must be a god of the dawn, the return of the morning light, then it would be the scarab delivering this golden gift.

Khepri is, in his own way, the great unifying god of the realms. He is chthonic, to use a Greek distinction made for gods coming from the darkness below, living in the underworld; but Khepri is also Olympian, of the celestial realms, being the god, whose might will lift the gold star of the day into our sky each morning. A darkness residing creature, Khepri is everything abject and impure in our bodies, made of shit and consuming shit, thriving within that which the world throws away. All that is lost, abandoned, deemed worthless and unworthy will sink to the bottom of the world and Khepri will feed on this and grow within it a newborn child. Khepri is also a self-created god, like Mithra, the Persian god born from a stone, a product of parthenogenesis, emerged whole from a lump of feces. Despite the popularity of the scarab ornament and the auspicious duty Khepri upholds by bringing forth the morning sun, there were no shrines or monuments built to this god in the ancient world, no cults formed in devotion to him, or at least none that have survived in the records. This is believed to be because Khepri’s role was one subordinate to Ra, the principal sun god of the Egyptians, and that Khepri was seen more as an aspect of Ra, like another solar deity, associated with the evening sun, Atum.

It could be that Khepri’s lack of prominence in the official rituals of ancient Egypt might have been because he is not the god of dualism, his existence stands in defiance of a distinct cosmos within which there is a line between the divine and the earthly materials of the world. At the same time, Khepri’s popularity within the ancient Mediterranean imagination, speaks to how the spirituality of the Bronze Age was more forgiving, flexible, and personal than that found in more modern manifestations of religion, such as the Abrahamic religions. In Gnostic or Manichean cosmology, just to use two examples that were competing for dominance over the polytheism of the ancient world in centuries gone by, there is a clear distinction made between the good of heaven and the evil of the created realm, the world within which we exist. This can also be extended to some Gnostic sects who would add that there is a distinction between the false world, that created by the Demiurge, according to Sethians for instance, and the true world, which would be where the unknown god resides, far from this sphere of illusion. A god such as Khepri, who is made of both feces and light, does not seem to make sense in cults of such separated polarities.

Unlike Gnostic or Christian cosmologies, however, the Egyptian systems of religion were incredibly flexible. Enduring for thousands of years, the Egyptian religion survived not by being rigid but by adapting and evolving. Khepri is a prime example of how far the definitions of the gods can be stretched by the ancient Egyptians, because his existence stands in contradiction to the more well-defined boundaries found in the world’s most popular religions today. Khepri is an embodiment of true nature, with all its contradictions and extremes. If we lay aside the idea that gods exist somewhere beyond the material world, and that truth is an ideal beyond any earthly form, we are faced with the natural world, containing the essence of heaven and hell combined within its manifestations. Khepri is the symbol of this unveiled existence; Khepri is the music of the spheres played within the shadows of a city sewer; Khepri is the derelict, the downtrodden, the most forlorn semblance of matter, a burned and abandoned corpse that is also secretly the vessel of the starlight, the moon, the sun and the secrets that keep the planetary bodies in harmony.

There is a limestone fragment from a Ptolemaic-era temple that shows Khepri, as the scarab, holding up the symbol for Duat, the underworld, or realm of the afterlife, of the ancient Egyptians. Khepri is flanked on either side by baboons who are dancing and screeching as they herald the sunrise. Baboons are sometimes also forms taken by the god of wisdom and writing, Thoth. Khepri rises from the underworld, the chthonic realm, into the sky with the blazing morning sun. The sun of dawn is shown here as a resurrection, a god risen from the crypt of the subterranean realm, living again in the sky for another day. The symbol for Duat is a five-pointed star inside a circle, designed in a way that is similar too but much simpler than the pentagram. The exact nature of the symbol’s relationship with the underworld is not known but it is believed that if refers to the solar cycle of Ra, as he passes through his elderly form, as Atum, and crosses over into death at night, descending into the underworld, which is the time when the night sky can be seen, and the stars glimmer above.

In the underworld of the dead there is starlight. The depths of the earth, where we can only go as spirits, contain skies and forests, mountains and lakes. The below realm is just as the above. One might think of the hermetic maxim, “as above, so below” when considering ancient depictions of the world below. The magickal meaning of correspondences, the heavens reflected on earth, should not always be interpreted so literally or directly. In the natural world we can see microcosms reflecting the same behavior as the macrocosms, but a deeper and more difficult message was being transmitted to us through the ancient esoteric teachings than that which is commonly associated with “as above, so below”. A more appropriate interpretation of this maxim is as a principle of emanationism; all things we are, perceive, and experience flow from another source beyond this dimension, whether we call that the Empyrean, Aeon, the Unknown God, Kether, Brahman, or any of its many names or understandings. The ancient Egyptians had a similar concept in their story of creation, where even the gods themselves were projections of greater, less defined, primordial gods who are referred to as the Ogdoad, or the eight-fold. The beings that comprised the Ogdoad, embodying such things as darkness, chaos, fluidity, and night, had begotten the gods and the world that we have inherited. The nature of such primordial origins is incomprehensible to us, but a simple way of thinking about this emanationism is to imagine that we are inside a movie being projected in a dark theater. We live inside this movie, not understanding who wrote or filmed it, not perceiving the machine that projects this fantasy on the screen, we exist as a shadow of a shadow, the dream had by a specter in another world. As characters in this shallow world of light, all we can do is awaken some suspicion in our souls that our origin lies elsewhere, somewhere beyond the story we are trapped in, beyond the screen, in an Eden we cannot imagine.

The underworld is not just a shadow emanation of the creator god, however, Duat was a real place for the Egyptians. In “The Book of Two Ways”, a coffin text from ancient Egypt, a map of Duat is included, showing its landscape is much like that of the earth. This map, painted on the inside of sarcophagi, was intended to guide the dead, along with “The Book of Coming Forth by Day”, through the underworld. While Duat is presided over by Osirus, the god of resurrection, it is Khepri, the rising sun, who actually escapes death each day. It is through eating death, through consuming and becoming waste, that Khepri transcends death. So, through this magick of devouring darkness and becoming the sun, Khepri is the spirit of transcendence through transgression; the god of light confronts and devours his own shadow side.

As we are emanations of the Aeon, so too is all of nature corresponding with the movements of the realms beyond. The dark grass does not rustle at night, the moonglow does not fill an empty window, and a noiseless spider will not crawl through the gossamer labyrinth of its home unless a divine word has been uttered on the other side or a great wave has passed through the Empyrean. The scarab beetle’s parchment wings separate and for a brief time, with the tickling sound of its flight like the riffle-shuffle of fifty-two playing cards, it lifts over the dazzling tapestry of sand hills and stones before returning underground again. In that one exalted flight, a god dies and is reborn. Those who were more attuned to the green language of the universe could see in this picture of nature a scripture written in the magick of the one beyond, the Aeon sending the light of a star in the form of scripture written as illusion. For those that clear the weeds from this ancient broadcast from a dream, now buried under the earth of many confused reinterpretations, the mind of the universe will open like the bare sky. Whether or not the stories told in the language of the birds are meant for us or not, however, remains to be seen.